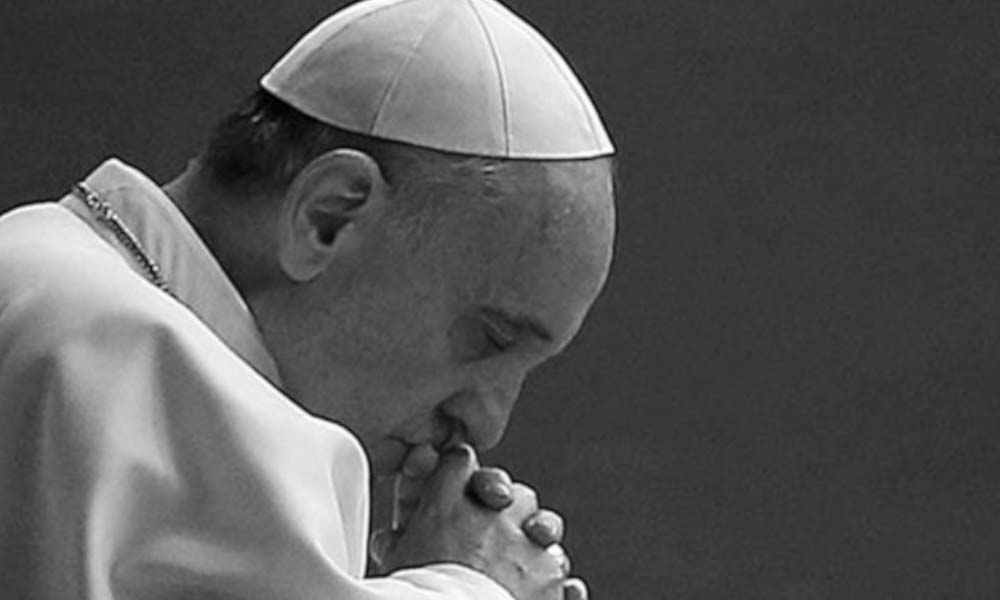

The death of Pope Francis marked the end of a papacy that often divided opinion but refused to be easily defined. His positions on poverty, climate, and inclusion drew admiration from some and concern from others. Yet when news of his death broke, something unexpected happened: people paused. Not in uniform grief, and certainly not in consensus—but in something quieter, more reflective. For a moment, the usual rhythm of argument and reaction slowed down.

This pause wasn’t just a matter of tone; it was visible in the real world. In Rome, thousands gathered at St Peter’s Square in the hours following the announcement. Pilgrims walked silently by candlelight, some holding wooden crosses, others weeping openly. A space better known in recent years for political posturing became, briefly, a site of shared stillness.

In Britain, more than a thousand people filled Westminster Cathedral for a requiem mass. Outside, passers-by stopped to pay respects at a photograph of the Pope surrounded by candles and flowers. Similar scenes played out in cathedrals across Europe. These were not just moments of Catholic devotion—they were moments of public reflection, notable in their cross-generational and even cross-belief character.

World leaders, regardless of ideology, responded in kind. Emmanuel Macron called Francis “a voice of peace.” Volodymyr Zelenskyy praised his “tireless calls for compassion.” Brazil’s President Lula said he was “a moral force in a time of moral uncertainty.” Closer to home, Prime Minister Keir Starmer described him as “a pope for the poor, the downtrodden and the forgotten.” King Charles spoke of his “tireless commitment to unity.” These tributes weren’t performative or partisan—they were unusually personal, and almost uniformly respectful.

In Australia, a federal election campaign was momentarily paused. Both the Prime Minister and opposition leader attended memorial masses. In an age when even a sporting event can become a political flashpoint, this kind of bipartisan gesture is striking.

Media outlets, too, broke form. The Financial Times, which rarely ventures into matters of faith, called Francis “a bridge-builder in an age of walls.” The Telegraph, often critical of his papacy, acknowledged his “moral seriousness.” Social media, which typically meets high-profile deaths with a barrage of instant opinions, was comparatively muted. The usual ideological trenches—culture warriors, campaigners, cynics—held back. There was a silence that, unusually, held.

This tells us something about the moment we are living through. We often say we’re a fragmented society, but that word doesn’t quite capture the mood. Fragmentation suggests quiet disconnection. What we actually face is fatigue—an exhaustion from permanent outrage, identity-based politics, and the endless churn of culture war skirmishes that make public life feel adversarial by default.

Pope Francis’s death, and the reaction to it, broke that rhythm. It reminded us—if only briefly—that we still share something. Not doctrine, necessarily. Not even belief. But recognition: that there are roles, and people, that still command a kind of moral weight. And that we are, despite everything, still capable of acknowledging it.

None of this means we are heading back to a golden age of consensus, assuming such a time ever existed. The arguments around Francis’s legacy—his handling of abuse within the Church, his cautious reformism, his ambiguous remarks on doctrine—will continue, as they should. But the mood around his death suggests that many are, consciously or not, searching for something deeper than the next ideological battle. A space where seriousness is not mistaken for solemnity, and silence is not seen as surrender.

It reminded us—if only briefly—that we still share something. Not doctrine, necessarily. Not even belief. But recognition: that there are roles, and people, that still command a kind of moral weight.

In a society increasingly defined by spd and spectacle, Francis offered something else: presence. He refused to reduce faith to faction, or human beings to sides. He often frustrated those who wanted quick answers or firm lines. But he offered, instead, a way of being that left room for ambiguity, complexity, and mercy. These are not qualities that trend well—but they last.

Perhaps that’s the real lesson in his passing. That we are not beyond redemption. That despite our divisions, we can still recognise the need for pause. That there is still a public appetite, however faint, for seriousness without theatre. And that figures like Francis, who speak softly in a loud world, may be remembered not for the wars they fought, but for the space they made possible.

In death, he may have done something his life never quite managed: revealed, if only for a moment, a vision of public life beyond the culture war. And in doing so, he offered a glimpse of the quieter strength we so often overlook.